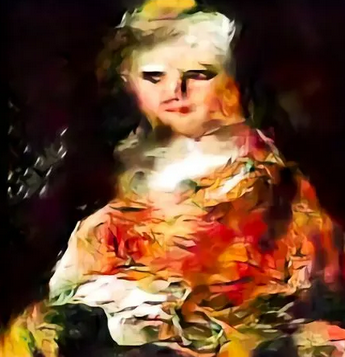

The gigantic art print is of a giant, glowing skull. Set against a drab and blurry background, the macabre icon reflects hues of ruby, electric blue, and charcoal. Depending on your interpretation, it could be burning, or perhaps backlit by some flame. The result is an artistic mash-up that seems at once neoclassical–but also abstract and surrealist.

Or maybe it’s just a fiery Terminator head. After all, the piece, entitled Faceless Portrait #5, was made by artificially intelligence. It’s part of a series entitled Faceless Portraits Transcending Time on display at HG Contemporary in New York.

So what does a machine know about mortality? That depends largely on how it’s programmed. The technical artist behind the effort is a neural network dubbed AICAN, short for Artificial Intelligence Creative Adversarial Network. It lives at the Art and AI Lab at Rutgers, where computer scientist Ahmed Elgammal has steadily fed it over 100,000 images spanning five centuries of artistic genres.

The exact way that artificial intelligence takes on creative projects can vary. Early on, for instance, some experts in the field focused on teaching machines to digest and reproduce distinct artistic styles, so that they could be applied to other images to make them look like Van Gogh or Picasso. That technique called “style transfer” is what’s behind web-based images like these Starry Night-style landscapes or these real time-lapse videos that could transform in and out of Picasso or Van Gogh mode.

Elgammal is doing something different. First, he asked AICAN to scan and analyze a vast body of artistic masterpieces to build a database of expert brushstrokes, themes, and imagery. Then he used what’s called an “adversarial network” technique to teach the machine to think up its own iterations. Adversarial networks basically give a machine two conflicting tasks, like a right brain versus left brain that will ultimately result in compromise.

In the most basic or “generative” form, an AI artist might tell its machine’s right brain to suggest art in some classic style or genre, while telling the left brain to reject anything that feels too similar to what the program has seen before. After repeated tries, the neural network adapts to start offering new images that fit the given parameters.

But Elgammal developed AICAN to go further. Instead of acting generatively, he asks it to be creative. To do that, he’s typically asked the neural net to create a new technique that riffs on many known styles throughout the ages but isn’t directly comparable to a specific one. It’s a mash-up technique, a way to hint at many known artforms, but also transcend them. (Here’s a look at some adaptations.)

For this portrait series, Elgammal deployed that creative adversarial network with the request that the result still resemble a portrait. Then he added one more wrinkle. For the portraits that riffed on life, Elgammal asked the machine to digest and adhere various formats of portraiture but also incorporate inspiration from 100 images of everyday people from the internet. For those about death, he did the same thing, but replaced the modern photos with pictures of about 100 skulls.

“We have two streams of data: inspiration and aesthetics,” he says. “The machine explores the space in between them. We’re giving artists more control of the process and pulling back on the autonomy.” The result is an assemblage of fairly trippy prints. Some show a face that’s blurred or swirling. Others look vaguely skeleton-like and macabre. Elgammal produced these in medium- and large-canvas formats up to about 5 feet, with prices between $10,000 and $22,000. “I’m always surprised by the results I get from the machine,” he says.

As with any good artist, AICAN is also capable of generating its own evocative titles for each piece. It uses a similar process: analyzing art titles, and figuring out whatever amalgamation based on the different influences, like Orgy and The Beach at Pourville. For this installation, Elgammal took control and kept it simple, with names like Faceless Portrait of a Queen. Entries in the skull-divined series are simply numbered, ergo Faceless Portrait #5. The idea is to leave room for viewer interpretations.

AICAN has collaborated on similar work before. In December 2018, for instance, it debuted several pieces with different artistic collaborators at Art Basel in Miami, including a unique mural about Charlie Chaplin. Elgammal has also conducted research that shows most people often can’t tell the difference between what’s man or machine made. When informed, they’ll definitely pay for the latter. In November 2017, the first AICAN print entitled St. George Killing the Dragon sold at auction for $16,000.

Elgammal hopes that giving the robot its own solo show in New York will continue to legitimize AI-inspired art. He often compares the technique to early photography, which was once first seen as a static tool for reproductions before becoming recognized for beautiful techniques. He’s also launched a business around it, earning an undisclosed share of each sale in a split with Rutgers. “We are basically a company who built this technology and work with artists to develop these projects,” he says. “Our goal is really to one day have this as available as a platform for any artist to make art using AI.”