Boom! and Bust, by Estelle Lovatt

McAlpine Miller captures such a sense of light in his paintings, so illuminated they make Times Square’s iconic giant animated billboards look dull. And makes a usually mirrorlike surface of a Jeff Koons sculpture appear in need of a good polish.

When I was invited to write this foreword, I tried imagining what McAlpine Miller’s new portfolio of artwork might look like. But so inventive is he, I couldn’t. Still, like a child at Christmas, I was eagerly waiting to open presents under the tree. In order to release, embrace and believe McAlpine Miller’s (un)imagined (im)possibilities, he retains an almost child-like gaze and joy of the world; to capture the zeal of childhood, that, when looking at his art, I feel like I’m Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’, and his canvases entertain me; as the Queen of Hearts says in Wonderland, “Sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast!” It’s hallucinations without drugs. Or, as Picasso said, “Everything you can imagine is real.”

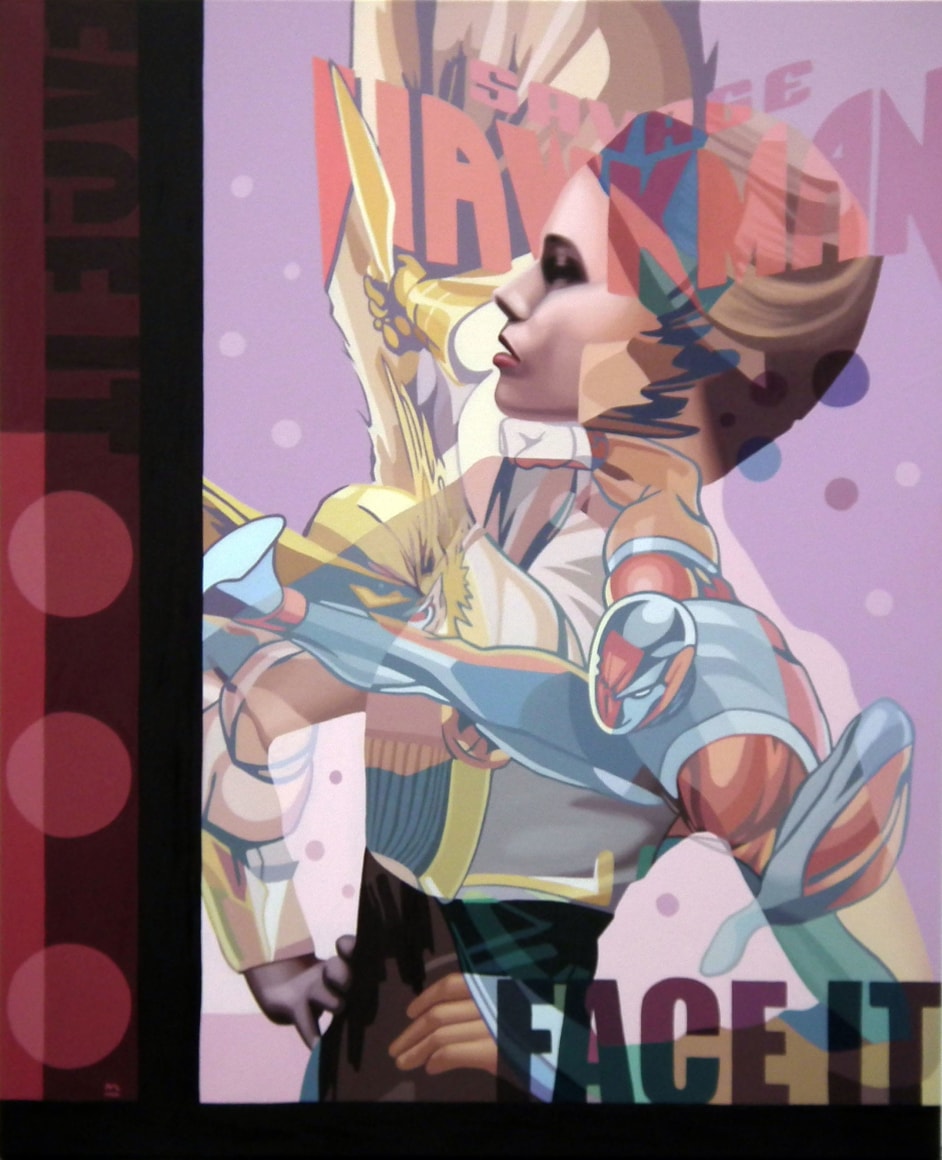

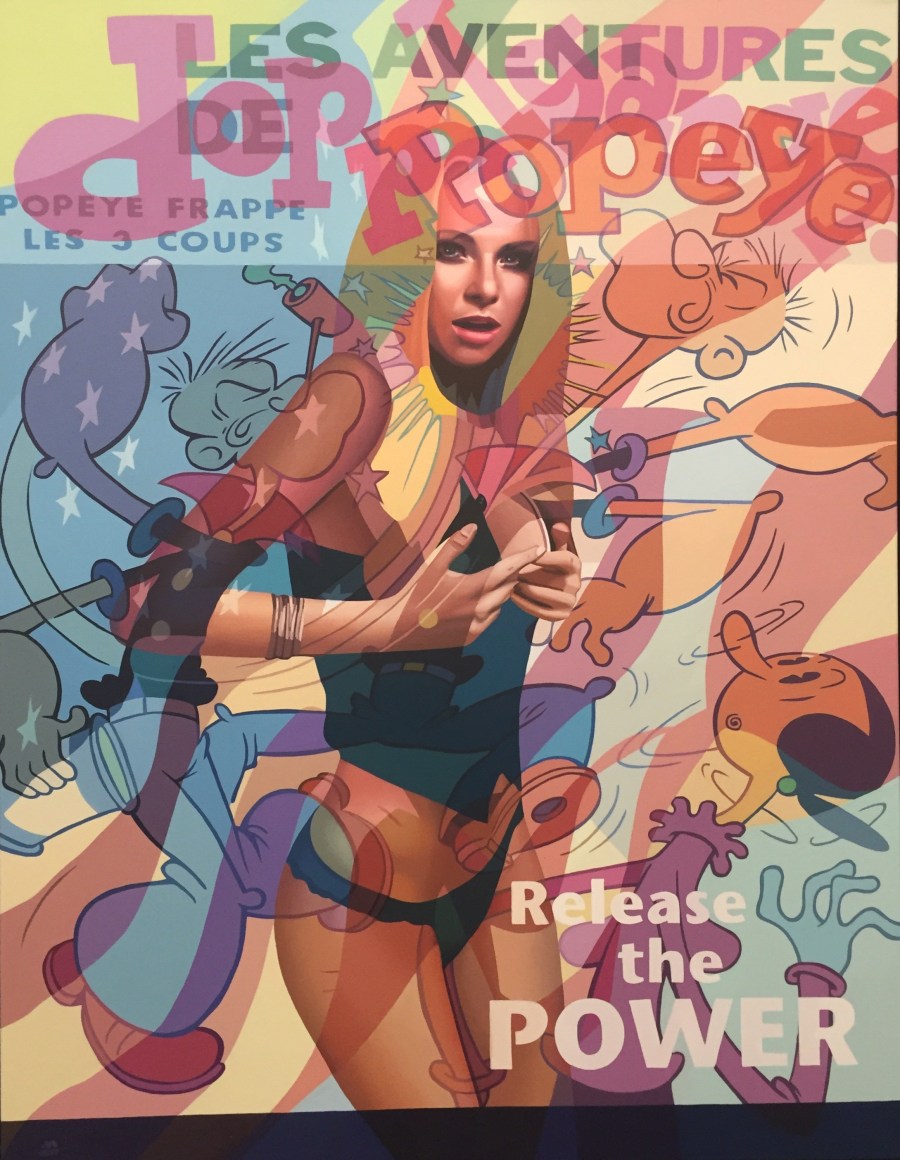

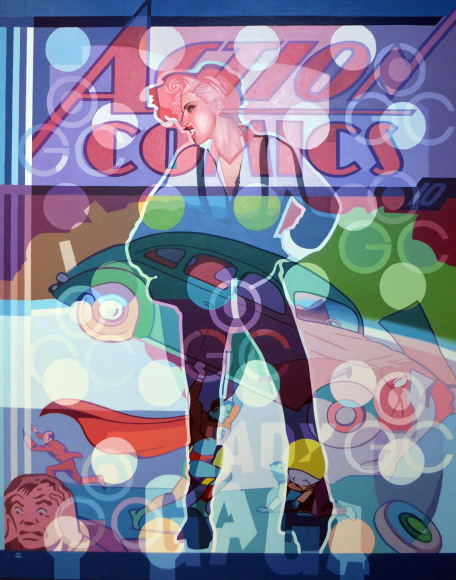

Looking at McAlpine Miller’s paintings it’s hard to believe the canvases are painted by hand -- using oil paints. Multi-layered, with a translucent quality, sharply drawn, each looks like it’s been computer generated, contrasted, linked together, photographed and scanned. And then again re-photographed and re-scanned, doing a diktat commenting about the globalisation of our consumer image culture. McAlpine Miller has one of the most creative minds in art today, and he’s established a process that follows no Masters. Creating his own genre – let me call it “Supernatural-Realism”.

A doyen behind the easel, affecting change and changing affect, he challenges 2D space towards a 4D Magic-Realism reality, where (dis)ordered fanciful goings-on show values philosophically, by juxtaposition of the real with the cartoon. Looking at his canvas is like watching a video game featuring Peter Max scuffling with Basquiat and Keith Haring scrapping with Ed Ruscha. Move over Thomas Kinkade, McAlpine Miller is today’s Master of Light. Notice the brightness of your backlit computer screen, tablet, cell phone and smart watch. Compare it to McAlpine Miller’s veiled multi-layers of paint in his canvas. His high-tech look is contemporary, vintage and retro. Revealing, in more ways than one, that which is see-through, enlightening and illuminating. I see new details in it every time I look at it. So I keep returning to it, as I do a favourite book.

Accomplished with technical genius, his attention to detail shows off his skill of illusion, hooked on a perspective, so curious in pattern, that his compositions are geometrically balanced in the abstract Divine Proportions of Fibonacci’s Golden Mean. What look like simple compositions are sophisticated, erudite, intricate and multifaceted. Technically skilled, his craftsmanship is phenomenal. Appearing like a collage photomontage. Relatively flat, overall realistic, highly detailed, precise transparency imitating technology; make the invisible visible and the see-through seen through layers, mimicking your Social Media, the illusions of distorted fact detached from reality. It’s sheer quality.

Strong drawing underpins his illusionist optical perspective. Old Master’s Classical draughtsmanship with an avant-garde Fauvist’s sagacity for hue, and a Futurists design, make McAlpine Miller timeless as he changes, adapts and produces imagery that goes back and forth in time as the pictorial space of his background, middle ground and foreground blend. Surreal in fabric, we are sucked in to his canvas as he incorporates the three qualities of the universe: time, space and material. With the three qualities of existence; the past, present and future.

McAlpine Miller is a Post-Modern picture maker of our dot com age. With roots in the Renaissance and the Dutch Golden Age, right up to Dadaism, Cubism, Op art and photography, his never-seen-before painting techniques create something beyond representational portraiture. And every time you look at a picture of his it works to make you feel like you’re a participant in the frame. His signature style is highly distinctive.

Through McAlpine Miller’s multi-layering of paint he creates extraordinary paintings inspired by 1950s America. Full of adventurous characters, based on the real-world of American comic imagery that we grew up with. Iconic 1950s Americana blended with European Romanticism. It speaks of American imperialism, politics, economy, military and its many cultural influences across the Pond of the Atlantic Ocean, flooding Europe. Keeping our mind on the American ways of American Exceptionalism and America’s place in the world.

Curious about this transatlantic world of ours, McAlpine Miller is part magician, part mathematician and part scientist. Working with the precision and clarity of a physicist, he’s the Richard Feynman of the art world. Not an artist, but one of the world’s greatest scientists, American, Feynman, a theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize winner, said, that he drew dancing girls to, “Explore the world! Nearly everything is really interesting if you go deeply enough. What I cannot create, I do not understand.” By the same physical laws of, what cannot be understood cannot be created, the natural mathematical beauty of aesthetics, in McAlpine Miller’s compositions, are (dis)covered with formulae. BOOM! – McAlpine Miller creates a feeling of (scientific) awe as he styles that which is impossible in science, as possible in art.

Absorbed by the muscle of outline and shape, intricately capturing and magnifying the world as inventively experimental, a patchwork of seemingly cut-and-paste layering - with oil paint and paintbrush, not Photoshop - of fictional superheroes from Marvel Comics and Hanna-Barbera to Walt Disney, that inspire us to be the best we can be, while playing a game of ‘doctors-and-nurses’ with your imagination. Take all this and mix it with a dose of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Bunny. In his canvas I always see something new I hadn’t seen before. Let us look: ‘She’ might wear an American Apparel t-shirt, Hollister panties, and sport a fashionable French-nail manicure. She is today’s Mary. As the artist believes, “Religion exists as a guideline. We disregard the science in favour of fantastical stories. And that’s what makes us human.”

Just as a Vermeer woman isn’t any particular woman, but any woman and indeed all women, so McAlpine Miller’s highly stylised, fashion(ed) Supermodel-types aren’t anyone, but they are everyone. Smiling as today’s Mona Lisa. Flirting with Rubenesque fantasies and desires. Her inner radiance glowing like she’s on fire, while she stands, high-heeled, revealing her midriff, while her bust, cleavage and underside of her breasts are exposed. Not objectified. Not weak. She is powerful. Aware of her sexuality highlighting her curves. The perfect girl, with natural sex appeal, that is open, and vulnerable, to suggestion. And in ‘The Right to Remain Silent’, much in the same way that Warhol’s film, ‘Blow Job’, shows details of voyeurism that might be pornographic, if this is what you see, then this is what you see. Botticelli did when eyeing up his beauty in ‘the Birth of Venus’.

But McAlpine Miller takes the gorgeous Cheerleader who lives next door and makes her more Flying Girl and ‘Darlin’ Doll’ of the U.S. air force troops. Particularly in ‘Drop Dead Gorgeous’ (is that an order, or compliment?), which could pay reference to the first woman to fly around the world, American, Jerrie Mock, with hints of Duchamp’s ‘Readymade’ rods, cylinders, spokes and wheels, with Dastardly and Muttley in their flying machines.

The king of today’s art world, McAlpine Miller is an extremely rare kind of artist, belonging to all generations, and balancing all art movements since the beginnings of western art, saving the Renaissance and challenging Abstraction. This is one of the reasons McAlpine Miller’s picture is open to so many different (re)interpretations. Paint is poetry and poetry is music and music is magic, and a McAlpine Miller picture reminds me of Walt Disney’s ‘Fantasia’ – the ‘classic’ film consists of different segments, edited together, producing a live-action concept of timeless action that’s so all-encompassing of all our senses, it reminds me of looking at a McAlpine Miller painting. He gets the adrenalin running a marathon, so I wouldn’t be surprised to see him designing theme parks next, for the thrill of it – for him, and us. There has to be references to the movies because every great artist has been influenced by the moving picture, even Degas, whose dancing ballerinas are inspired by the frames and long shots of early cinema. Here, McAlpine Miller, employs moths, linked with the omen of death, from Thomas Harris’s film, ‘The Silence of the Lambs’, with Hannibal Lecter, against the butterflies, signifying beauty, fragility of life, the resurrection, regeneration, fortune and love from Christian symbolism. That even Donald Duck might be seen as one of Jesus’s early disciples, a fisherman showing his family Huey, Dewey and Louie, to accent a Christian life, intoning to his family to, as Christ said, “come, follow me”. While two Popeye’s play with his conscience suggesting we have two sides to our personality; the good one people see and the bad one we hide. And two nurses double the fantasy.

Then, like an unexpected curveball in baseball, thrown off to the side, in some of his canvases, down a strip on one edge, there’s an asymmetrical reference to De Stijl, and the New York of Mondrian’s ‘Broadway Boogie-Woogie’. I never get bored of looking at McAlpine Miller’s artwork. And neither will you. As he catches your memories and dreams faster than Cupid’s bow shoots his arrow of love. The 20th century had Norman Rockwell’s all-American girls, the 21st century has McAlpine Miller’s. From American, Charles Dana Gibson’s, ‘Gibson Girl’ to today’s cheer-leader babe asking if a superheroine ‘Wonder Woman’ will be in the White House in 2016? Depending on what side of the political white picket fence you’re on, the woman in the painting is, to you, a Hillary Clinton or a Carly Fiorina. Only sexier. Slimmer. Fitter. A Boadicea or Betsy Ross sewing the American flag, in white underwear.

In ‘Cake Free II’, visions could be turning Biblical in our consumer society as drama is painted over a Caravaggio-esque ‘Doubting Thomas’ table – but look closer, as McAlpine Miller suggests, “when all around there is joy and fun we can somehow feel isolated and alone.” He continues, “This is another element of humanity which seems to survive with greater power today than at any other time, as we drift deep into our own thoughts; thoughts which have no real regard to the reality which we live. This can create disillusioned individuals; people unhappy with their lot and perhaps prepared to alter their natural path in life.”

Look behind ‘Iron Woman’, see Dali’s, ‘Christ of Saint John of the Cross’, with a Church stained-glass look to its surface breaking through to the suggestion of a Christian altar painting. Suggesting He died to save you/us, gives you the sense that as you recognise each motif in each image you are also recognising the reflection of yourself in it as well. In ‘Bath Time Selling Point’, the Christian religious rite symbol of Baptism is there as a life-saving command, if you want it to be, as McAlpine Miller shows, “the cleaning process. If something of a ritual. And we create unhappy situations and attempt to eradicate these ‘stains’ by ‘bathing our souls’. We have all done things which we later regret! And gradually forget, only to replace with another episode.”

The US-UK special relationship is explored in ‘Space Invader’, as a European-looking girl is wearing a British gentleman’s bowler hat and braces (suspenders in American English). Across the foreground are the title lyrics of the song, ‘Don’t Stand So Close to Me’, written by Sting, of The Police. Dealing with mixed feelings of lust, fear, guilt and inappropriateness leading to confrontation of a ‘Lolita’ mixed with Gary Puckett’s (& The Union Gap) ‘Young Girl’.

McAlpine Miller’s compassion for Americana, and ‘The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave’, speaks the commonplace language of everyday people, and reminds me of Shakespeare’s ‘Richard II’ - when King Richard says, “throw away respect, tradition, form and ceremonious duty, for you have but mistook me all this while: I live with bread like you, feel want, taste grief, need friends: subjected thus, how can you say to me, I am a king?” In other words, it’s all about fitting in and belonging. As we all hope to. With two kinds of light in his paintings; day light and your internal, spiritual, light - the one that allows you to dream.

McAlpine Miller uses the Stars and Stripes and Union Jack and, just as we question whether a Jasper Johns ‘Flag’ is a flag, or a painting of a flag, or simply an image of a common, instantly recognisable symbol, McAlpine Miller looks at, “the flag as a symbol of relationships and friendships, in a similar way to how the models and comic characters relate.” So, in eye-catching, overlapping graphics, the integrated intertwined flag is a new motif internalising height, width and depth.

In to his typically Renaissance Chiaroscuro palette he mixes today’s Pantone neons producing glazes from flesh pink to taxicab yellow, burnt sienna brown to soda pop orange, chromium of oxide green to Blue’s Clue blue. Or innocent sex-bomb-red like Betty Boop, who, as small as she is, projects a huge amount of self-confidence. As does Maid Marian, the love interest to the English hero Robin Hood, giving him his horn, while robbing from the rich and giving to the poor. As we know, rooted in the glamour of Pop art, from Warhol to Lichtenstein, intellectually and emotionally, there are issues with the commercial commodity of capitalism. Bang! A Genesis-like beginning, abstruseness and semiotics of meaning are pictorially interpreted, to shuttle between the American and the European culture, political discourse and symbolic totems.

A comical reflection of society, with not one focal point, but many, the energy in McAlpine Miller’s artwork is both believable and unbelievable simultaneously. Now, to help society, instead of having him paint on a canvas, he should be painting a huge mural on the exterior of a building in NYC, celebrating President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) that helped lift people’s mood during the Great Depression. After all, we are in another.

As a modern day art-deity McAlpine Miller is an Old Master-in-Waiting.